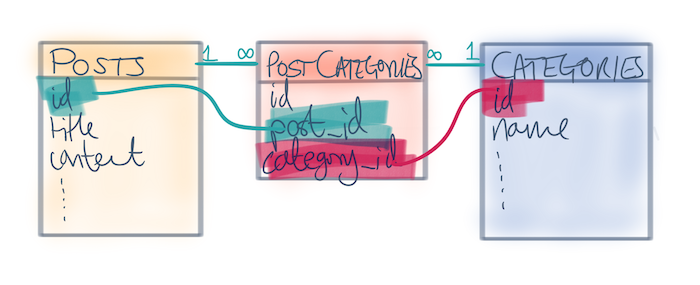

In object-relational data modelling, the ‘has-and-belongs-to-many’ paradigm is very common. For example if you were modelling posts and categories, you might say that a post can have multiple categories, and each category can be used for more than one post.

A common approach to creating this relationship in a database is to use a join table.

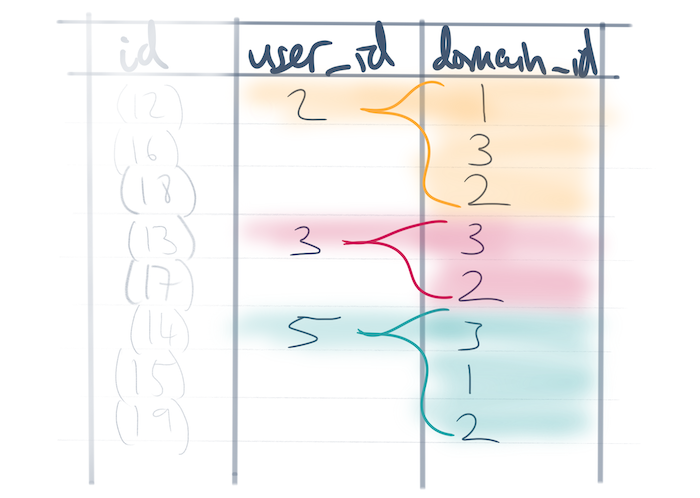

In carolus, the Ruby on Rails app that runs raywenderlich.com, content is categorized into one of several “domains”, currently iOS, Android, Unity and Unreal Engine. Users have the ability to follow a domain, thereby personalizing the content they see on their homepage. This is a classic example of ‘has-and-belongs-to-many’ modelling, with the following structure:

This feature has been available for long enough that lots of people now follow their chosen domains, and I was interested in the answer to the following question:

Are people interested in more than one domain? And if so, which domains are most commonly enjoyed together?

Or, framing the question in something more akin to flamewar-inciting clickbait:

Do people actually admit to liking both iOS and Android?

The Naïve Approach

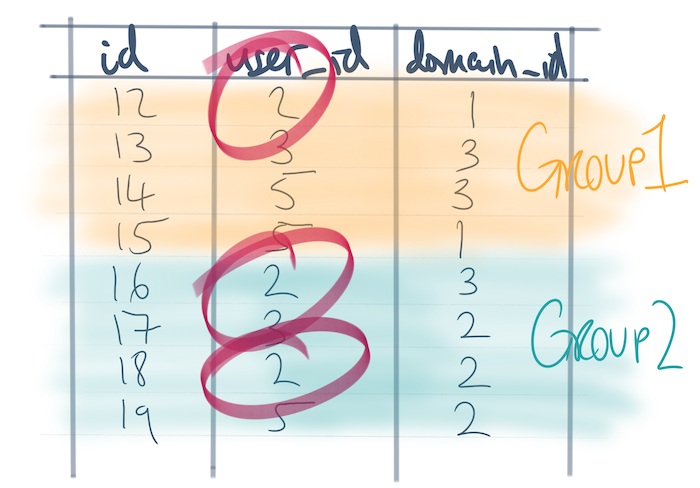

The answer to this question involves looking at the domains each user has marked as interests, and then counting how often each combination appears.

First let’s enumerate each of the possible domain combinations and create a hash to store the counts:

ids = Domain.pluck(:id)

combinations = (0..ids.length).flat_map { |l| ids.combination(l).to_a }

.map { |c| Set.new(c) }

domain_combination_counts = combinations.map { |combination| [combination, 0] }.to_h

This uses the #combination method on Array to generate every possible combination of the domain ids, converting it into a Set. Then it creates a Hash with each value being one of the domain combinations, and the value being the count of users that have selected the equivalent set of interests.

Once this Hash has been pre-populated with zeros, ActiveRecord makes populating it easy — loop through all the users, and record the list of domains marked as interesting:

User.all.each do |user|

domain_ids = Set.new(user.domains.pluck(:id))

domain_combination_counts[domain_ids] += 1

end

This approach is simple to reason about, and is where I first started on this project. However, I quickly discovered that it suffers from several downsides:

- It requests all the

Userrecords up-front from the database. - It then instantiates each of the individual

Userrecords as an object in Ruby, even though it doesn’t use it. - Finally, it requests the

interestsfor a user (i.e. the join table) one-at-a-time. This means many, many round trips to the database.

There are several approaches you could take to address each of these. We’re going to start with the first one — let‘s not request everything up-front.

Batching Query Results

When you perform a query such as the above, which loops through every record in a large result set, Rails requests all the records at once, and then instantiates them as ActiveRecord objects in memory. This can be extremely memory intensive. In fact, when I first ran the above query, I very quickly ran out of memory allocated to the docker container.

Rather than requesting all the results at once, Rails offers a built-in way to retrieve results in smaller batches, increasing the number of database requests, but reducing the memory overhead.

find_in_batchestakes a block that acts on a group of records (i.e. the entire batch).find_eachunbundles the batch into individual records, and passes each one to the supplied block. This has the same semantics as#each.

Using find_each results in a very subtle change to our loop:

User.all.find_each do |user|

domain_ids = Set.new(user.domains.pluck(:id))

domain_combination_counts[domain_ids] += 1

end

This pulls users from the database in batches of 1000, and then iterates through each of them. The :batch_size argument gives you control over the batch size.

Retrieving users in batches like this reduces one part of the problems with the original approach — we no longer need to retrieve and instantiate records for all our users at once. Instead, we do them in batches of 1000, resulting in a much lower memory requirement.

However, why are we instantiating User objects anyway? We don’t care about the users, just their interests.

Get the Database to do the Work

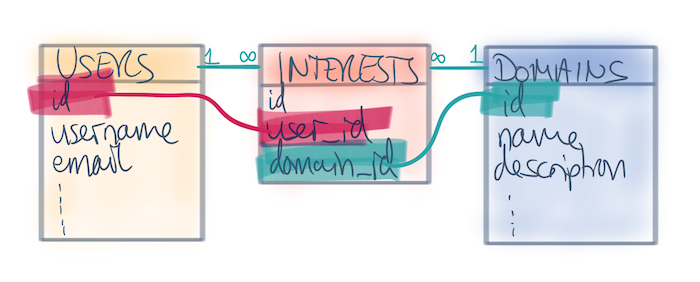

The interests table is the join table between users and domains, and as such has user_id and domain_id fields. We’re interested in which domains each user is interested in, and as such all the information we need is provided in this single table.

We want a list of domains for each user, i.e. a list of the domain_ids grouped by user_id:

Interest.group(:user_id)

.select('array_agg(domain_id) as domain_ids')

.each do |user_interest|

domain_ids = Set.new(user_interest.domain_ids)

domain_combination_counts[domain_ids] += 1

end

The #group method in ActiveRecord is underpinned by the SQL GROUP BY method and tells the database that each result row should represent all the records for that single, unique user_id. Then the select method uses some SQL to combine all the rows for the given user into an array.

Note: The

array_agg()method is available in PostgreSQL, but might not be in other databases. It’s one of the aggregate methods available when usingGROUP BY.

The result returned from the database will have a single column, named domain_ids, of an array type. Rails converts this array type into a Ruby array type, giving us access to an array of domain ids for each user — precisely what we wanted.

This approach has reduced the memory overhead in Ruby, and the number of requests that need to be sent to the database. However, it still creates an object for every single user that has expressed an interest in a domain. This could be a lot of memory, luckily we already know the solution.

You’ve Got to Batch it up Baby

…before it falls apart at the seams

When we solved this problem before, we switched to batching up result sets — don’t request all the results at once, just get a small batch of them. It seems reasonable to do that again, right?

The problem is that batching in Rails is predicated on using the primary key to select batches. Results are sorted and then selected based on this key. This will not work with results that are grouped — you need to ensure that all the rows for a given group appear in the same batch of results, otherwise the aggregate value will be incorrect.

However, we can take the spirit of batching, and instead batch on the field we are grouping on, in this case the user_id. To do this, we create a concern on a model:

module GroupBatchable

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

included do

def self.batch_on_group(key = nil, batch_size: 1000)

raise 'You must specify a key on which to group and batch' if key.blank?

raise 'You must supply a block to be executed on each batch' unless block_given?

upper_bound = order(key => :desc).limit(1).pluck(key).first

batch_start = 0

while batch_start < upper_bound

yield group(key).order(key => :asc)

.where(key => batch_start..(batch_start + batch_size - 1))

batch_start += batch_size

end

end

end

end

This adds a new batch_on_group class method to any models that include this concern. This performs the same batching operation that in_batches does on ActiveRecord, but combines it with a group operation too.

To use this, include it in the Interest model:

class Interest < ApplicationRecord

include GroupBatchable

belongs_to :domain

belongs_to :user

end

The query then becomes:

Interest.batch_on_group(:user_id, batch_size: 1000) do |batch|

selected = batch.select('array_agg(domain_id) as domain_ids')

domain_ids = Set.new(selected.domain_ids)

domain_combination_counts[domain_ids] += 1

end

The block yields an ActiveRecord relation that is pre-grouped and represents a batch of results. We add the select method to specify the result we want to acquire, and then the rest is as before.

This final query here is a little more complex than the initial one, but significantly more efficient. It pushes off as much of the data munging work to the database as possible, and keeps the memory overhead in Ruby to a reasonable level.

It’s also significantly faster. Solving a similar problem to this (with a more complex set of join tables between the two tables of interest) took over an hour with the initial version of the query. The batch_on_group version took less than 10 seconds.

Enough with the theory

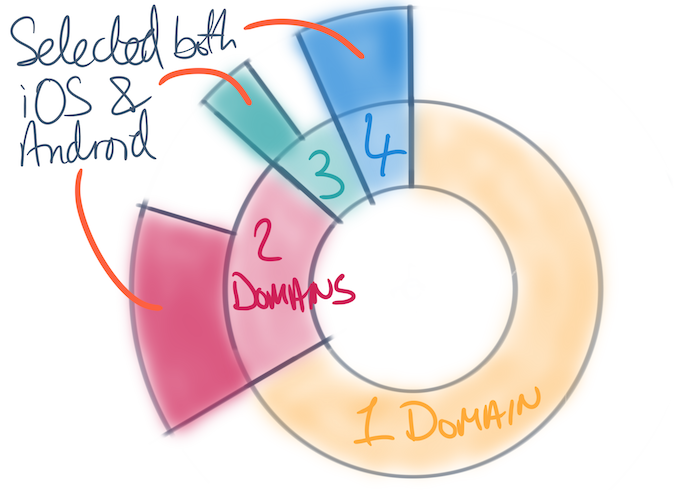

Now you’ve skimmed all that, it’s only fair that I answer the question: “Does anybody actually like iOS and Android?”

- Approximately 1/3 of users with interests have selected more than one domain.

- Of those with more than one interest, approximately 70% have selected both iOS and Android.

This same approach can be used to determine other interesting relationships as well, and is easily adapted to work on any ActiveRecord ‘has-and-belongs-to-many’-style relationship, irrespective of the number of tables required to make the join. For example, we can run a similar analysis on the model we use to allow users to track their progress through content — they’ve said they like two domains, but do they actually watch videos from both sides of the fence?

Hopefully you’ll find GroupBatchable useful in your own code. Say hi on twitter to let me know if you do, or if you have any questions.

Writing code, solving problems and entertaining the masses